meta data for this page

Simatic variable types

Bit & Byte

The Bit is the simplest form; it's a signal that can be true or false, with its official English equivalents being “TRUE” or “FALSE,” or even simply 0 or 1. There is no 2 anymore because two is represented by 10 according to the rules of the binary number system, which in this case is not ten but one zero. To clearly distinguish this, we write numbers in the decimal number system “just like that,” for example, 10. If this is a number in the binary number system, then we denote it as 2#10.

The Bit is the simplest form; it's a signal that can be true or false, with its official English equivalents being “TRUE” or “FALSE,” or even simply 0 or 1. There is no 2 anymore because two is represented by 10 according to the rules of the binary number system, which in this case is not ten but one zero. To clearly distinguish this, we write numbers in the decimal number system “just like that,” for example, 10. If this is a number in the binary number system, then we denote it as 2#10.

The decimal number system stems from the fact that we have ten fingers and, historically, used them to perform all our calculations. If we had, say, three fingers on each hand, meaning six in total, then we would be using the six-number system now. Computing is based on the above yes-or-no logic, i.e., the binary number system, which is why we often use the hexadecimal number system. I'll talk about that later. Let's first look at the binary number system through a byte to see how it works.

A byte is a variable type consisting of 8 bits. The value stored in it must be somewhere between 0 and 255, depending on the bit positions. The example below may help you understand this a little:

Let's take the bit sequence “01010110” as an example, which fills the above byte. The bits of a byte are always numbered from right to left; position 0 is always on the right. Each position corresponds to a given power of the binary number system; position 4 corresponds to 24 = 16. If there is a 0 in this position in the example, then it does not “count”; if there is a one, then its value “counts”, and as can be seen in the rows marked in green, the sum of the “counting” rows gives the current decimal value of the byte, 86. That is, 2#01010110 = 86.

Therefore, the byte reaches its maximum value when all bits are set to 1. It can be calculated that 2#11111111 = 255. The byte data type holds values between 0 and 255.

In computing, we use the base-10 number system, as well as the binary and base-16 number systems. The values described in it are called hexadecimal numbers and are denoted by the prefix “16#” or sometimes “hex#”. Sometimes the hexadecimal number system is simply the hash, like this: “#ABCD”. The hexadecimal number system changes order of magnitude at 16, meaning that a position can contain a value between 0 and 15. This can be very confusing in the base 10 number system, so the two-digit positions are denoted by letters:

10 = 16#A

11 = 16#B

12 = 16#C

13 = 16#D

14 = 16#E

15 = 16#F

If a byte reaches its maximum value, meaning every bit is set to “1”, then: 2#11111111 = 255 = 16#FF

If we calculate: F, i.e., “15” * 16 + “15” = 255

In some ways, this can make our lives easier, because if we see a value of “16#FF” somewhere, or a longer series of these, for example “16#FFFF_FFFF”, then we can suspect that we have reached the maximum value of one of the variable types. I would also like to mention the 8-bit, i.e., octal number system, it sometimes still occurs here and there, for example, in the case of numerical symbols, but only rarely, we don’t really use it.

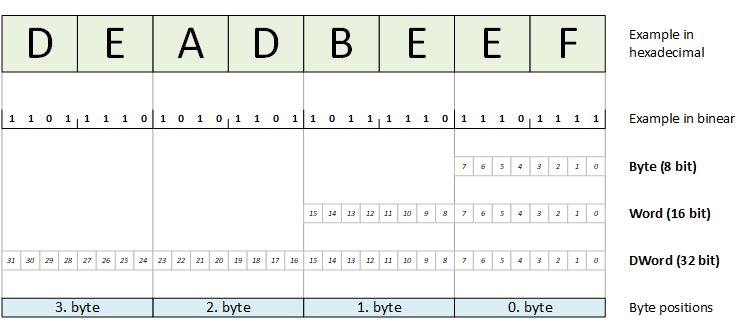

DEAD_BEEF

Just as “FF” is likely to represent the maximum of a given variable type, dead beef is a test value designation, a play on letters. The letters of the hexadecimal number system are a, b, c, d, e, f. #dead_beef contains all of them except c, so it is helpful for testing. The Windows calculator, switched to programmer mode, is very helpful for hex-dec-bin conversions. From this, it turns out that the value of 16#dead_beef is:

More information:

TIA Datatypes: S7 data types summary table

BYTE – WORD type variables

There are plenty of variables in the world of automation. They differ in scope (size) and internal structure depending on their use.

The simplest variable types have no internal structure, i.e., they can describe ones and zeros in different scopes:

The longest 64-bit LWord didn't fit in the example above, but I think it's relatively easy to imagine. The byte positions are on the bottom row. If everything works well, this is the byte order for the longer variable types, but sometimes confusion arises in the matrix, and this order gets “tangled”.

This most often happens when we try to transfer long variables via communication to other systems, such as HMI. In such cases, it is definitely worth testing the transfer, for example, with the above trick, because when the specified #deadbeef is on one side. If the destination side shows #beefdead or #efbeadde, we can rightly suspect a conversion discrepancy, which is easiest to correct on the starting side by swapping the structures.

The following types are unsigned (UNSIGNED), meaning their minimum value is always zero.

Let's review the basic variable types and their features:

| Type | Bit | Min. | Max. | Value range HEX | Value range DEC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BYTE | 8 | 0 | 28-1 | 0 .. FF | 0 .. 255 |

| WORD | 16 | 0 | 216-1 | 0 .. FFFF | 0 .. 65.535 |

| DWORD | 32 | 0 | 232-1 | 0 .. FFFF_FFFF | 0 .. 4.294.967.295 |

| LWORD | 64 | 0 | 264-1 | 0 .. FFFF_FFFF_ FFFF_FFFF | 0 .. 18.446.744.073.709.551.615 |

Any rules do not bind the contents of the above variables; they actually only contain some bit combinations. They can't have negative values by default; INT type variables are used for that.

More information:

TIA Datatypes: S7 data types summary table

INT type variables

In the case of the INT, which is the integer type, the definition becomes slightly more complex in terms of formal constraints because of the introduction of the sign bit. This means that the highest value of the variable's position, the first bit on the left, will represent the sign: if it is “1”, the variable indicates a negative number, whereas if it is “0”, it indicates a positive one.

Really, just for completeness, in the case of negative numbers, the program uses the so-called “two's complement” representation. That is, it first negates all the bits of the numerical value, i.e., it converts 0 to 1 and vice versa, and then adds 1 to the resulting value. This conversion means that the negative value cannot be read directly from the bit combination unless the conversion is performed again in the opposite direction:

As a result, Simatic only uses binary and hexadecimal notations for positive numbers, meaning that negative hexadecimal or binary values will not show the actual numerical value but instead the value based on the bit pattern. For example, A, which equals ten, will still be 16#A, but -A, which equals -10, will be displayed in WORD format as FFF6. This misunderstanding is resolved by the rule that hexadecimal and binary signals cannot have negative values in Simatic:

In the above example, I tried to assign a value to an INT variable. It is clear that the compiler accepted the negative value when specified in decimal, but not when specified in hexadecimal or binary. Let's look at the contents of the INT variable in several forms:

| DEC | SINT HEX (8-bit) | SINT BIN (8-bit) | INT HEX (16-bit) | INT BIN (16-bit) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 16#7F | 2#0111_1111 | 16#007F | 2#0000_0000_0111_1111 |

| 1 | 16#01 | 2#0000_0001 | 16#0001 | 2#0000_0000_0000_0001 |

| -1 | 16#FF | 2#1111_1111 | 16#FFFF | 2#1111_1111_1111_1111 |

| -85 | 16#AB | 2#1010_1011 | 16#FFAB | 2#1111_1111_1010_1011 |

| -128 | 16#80 | 2#1000_0000 | 16#FF80 | 2#1111_1111_1000_0000 |

The INT type is optimized for decimal handling; it can also be used in hexadecimal and binary forms, but in these cases, you need to pay close attention to the type's special characteristics.

Compared to byte and word type variables, this means that the maximum value of these variables is almost halved when dealing with decimal numbers. However, roughly the same magnitude can be used in the negative direction. For example, a one-byte-long SINT type will operate within the range -128 to 127, unlike the “plain” BYTE range of 0 to 255.

The letter “S” in the SINT definition stands for the word “short”, as the INT type is the default integer (16 bits), while SINT is short, with half the bit length—8 bits. The letter “D” represents the word “double,” with its 32 bits.

| Type | Name | Bit | Minimum | Maximum | Value range HEX * | Value range DEC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SINT | short integer | 8 | -(27) | 27-1 | 0 .. 7F | -128 .. 127 |

| INT | integer | 16 | -(215) | 215-1 | 0 .. 7FFF | -32.768 .. 32.767 |

| DINT | double integer | 32 | -(231) | 231-1 | 0 .. 7FFF_FFFF | -2.147.483.648 .. +2.147.483.647 |

| LINT | double long integer | 64 | -(263) | 263-1 | 0 .. 7FFF_FFFF_ FFFF_FFFF | -9.223.372.036.854.775.808 .. +9.223.372.036.854.775.807 |

* Negative number ranges are not supported in hexadecimal and binary formats.

UINT type variables

The unsigned UINT type (the letter U stands for unsigned) removes the hassle of dealing with negative values from the world of the INT type. It corresponds to basic types like BYTE, WORD, etc., in terms of value range, but with INT it indicates that we want to treat the contents of the variables as numeric values.

| Type | Name | Bit | Minimum | Maximum | Value range HEX * | Value range DEC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USINT | unsigned short integer | 8 | 0 | 28 | 0 .. FF | 0 .. 255 |

| UINT | unsigned integer | 16 | 0 | 216 | 0 .. FFFF | 0 .. 65.535 |

| UDINT | Unsigned double integer | 32 | 0 | 232 | 0 .. FFFF_FFFF | 0 .. 4.294.967.295 |

| ULINT | Unsigned long integer | 64 | 0 | 264 | 0 .. FFFF_FFFF_ FFFF_FFFF | 0 .. 18.446.744.073.709.551.615 |

* Negative number ranges are not supported in hexadecimal and binary formats.

More information:

TIA Datatypes: S7 data types summary table

REAL type variables

REAL type variables (REAL, LREAL) are defined by the IEEE 754 (IEEE 754/1985 Floating Point Number Format) standard. This is a fairly complex type that, despite its intimidating complexity, is well-suited for storing fractional numbers.

If you are interested in the definition of the type, please look it up on Wikipedia, for example, because I can't; I can't explain how this type works simply.

- Sign: The sign is determined by one bit (red color). This bit can be either “0” (positive) or “1” (negative).

- Exponent: The exponent ranges from 128 to -127.

- Mantissa: Only the mantissa is a fractional part of the overall value.

| Type | Bit | Value range DEC |

|---|---|---|

| REAL | 32 | -3.402823e+38 .. -1.175 495e-38 .. +1.175 495e-38 .. +3.402823e+38 |

| LREAL | 64 | -1.7976931348623158e+308 .. -2.2250738585072014e-308 .. +2.2250738585072014e-308 .. +1.7976931348623158e+308 |

In practice, REAL is suitable for handling fractions and large values. Due to its nature, it is mainly used for processing and evaluating measurements. It is important to note that, because of its structure, if a very large value is stored in it and we try to increase or decrease it by, say, a very small value, nothing will happen; the stored value will not change. The type is inherently not suitable for handling exact counters, since it handles numbers “in order of magnitude.“ INT is more appropriate for counting functions.

More information:

TIA Datatypes: S7 data types summary table

If you'd like to support the development of the site with the price of a coffee — or a few — please do so here.

If you'd like to support the development of the site with the price of a coffee — or a few — please do so here.

CHAR type variables

CHAR (character) types are suitable for storing a single letter each. The original CHAR uses codes from the ancient ASCII character mapping table. This table contains a mix of 255 different characters (letters, numbers, control characters, graphic symbols). Its advantage is that it requires only 1 byte, but its disadvantage is that the character set is quite limited; for example, Hungarian or Chinese accented characters are mostly excluded.

The extended version of CHAR is WCHAR (wide-character), which has a 2-byte length but can be used more broadly with its (UNICODE) UCS-2 mapping. Up to 65,535 character mappings can be encoded with 16 bits; UNICODE does not fully utilize this range.

When declaring an operand of data type WSTRING you can define its length using square brackets (for example WSTRING[10]). If you do not specify a length, the length of the WSTRING is set to 254 characters by default.

| Type | Name | Bit | Code table | Value range HEX | Value range DEC | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHAR | character | 8 | ASCII | 0 .. FF | 0 .. 255 | 'P', CHAR#'P' |

| WCHAR | Wide character | 16 | UCS-2 | $0000 - $D7FF | 0 .. 55.295 | WCHAR#'Ő' |

Special characters

A character string can also contain special characters. The escape character $ is used to identify control characters, dollar signs and single quotation marks.

| Character | Hex | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| $L or $l | 000A | Line feed | '$LText', '$000AText' |

| $N | 000A and 000D | Line break The line break occupies 2 characters in the character string. | '$NText', '$000A$000DText' |

| $P or $p | 000C | Page feed | '$PText', '$000CText' |

| $R or $r | 000D | Carriage return (CR) | '$RText','$000DText' |

| $T or $t | 0009 | Tab | '$TText', '$0009Text' |

| $$ | 0024 | Dollar sign | '100$$t', '100$0024t' |

| $' | 0027 | Single quotation mark | '$'Text$'','$0027Text$0027 |

STRING type variables

STRING also has two subtypes, just like CHAR. The old, “old-school” STRING, which describes the text with ASCII characters, and WSTRING, which uses WCHAR characters with two bytes per character. Both types are suitable for storing text, which can be extremely useful for communication, especially in HMI connections.

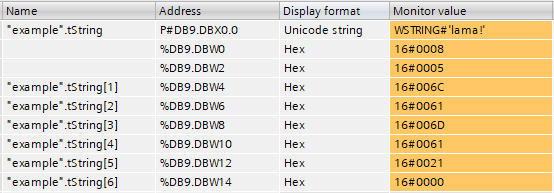

For both types, the first two positions show the maximum length of the given STRING and the current length it has been filled with. One position equals one byte for STRING, and one word for WSTRING.

In the example above, taken from the PLC status, I entered the phrase “lama!” into an 8-byte STRING variable. The first two bytes contain the maximum length of the STRING (8) and the current length (5), followed by the phrase as our message.

If I change the display format to hexadecimal for the characters, I see the ASCII code for each letter.

That is, the letter “l” is ASCII 16#6C, and “a” is ASCII 16#61, … For WSTRING, this assignment appears like this:

The “$00l” content type is due to the nature of UNICODE, as “simple” characters do not fill the entire UCS-2 space. It is clear that while we counted the positions per byte above, in this case each position occupies a word. The first two words here also contain the maximum length of the STRING (8) and the current length (5).

The same definition is given in hexadecimal form as follows:

If we fully fill in the UCS-2 word field, we can see what the “non-simple characters” look like. In the first step, I entered longer codes in the word variables per character (1), and from this the “example” WSTRING (2) was displayed:

To sum it all up:

| Type | Length | Character encoding | Length (characters) | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STRING | 2 byte + text | CHAR, ASCII | 0 .. 254 byte / character | 'lamaPLC', STRING#'lamaPLC' |

| WSTRING | 2 word + text | WCHAR, UNICODE | 0 .. 16382 word / character | WSTRING#lamaPLC |

More information:

TIA Datatypes: S7 data types summary table

TIME type variables

TIME types mainly serve for timing purposes. The most common type in programs is simple TIME, such as in connection with IEC timings, like this:

These will be discussed later, but in the example above, the time (PT) is specified in TIME format, with 12 seconds written as t#12s.

TIME is a DINT type variable that stores time in 32 bits, measured in milliseconds. The stored value can be positive or negative, and the rules for negative integers apply, meaning negative TIME values cannot be represented in hexadecimal or binary form.

The same rules apply to the LTIME type, but it stores nanoseconds in an LINT variable, using 64 bits. Interestingly, the maximum value of LTIME is 106,751 days, or about 292 years.

The S5TIME type was included among the variables for downward compatibility; it was the default (and only) time type during the S5 PLC era.

| Type | Length (form) | Value Range HEX | Value Range DEC | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIME | 32 bit (DINT) | 0 .. 7FFF_FFFF | T#-24d20h31m23s648ms .. T#+24d20h31m23s647ms | T#12s, 16#ABCD |

| LTIME | 64 bit (LINT) | 0 .. 7FFF_FFFF_ FFFF_FFFF | LT#-106751d23h47m16s 854ms775us808ns .. LT#+106751d23h47m16s 854ms775us807ns LT#12s | LTIME#12s, 16#ABCD |

| S5TIME | 16 bit | S5T#0H_0M_0S_0MS .. S5T#2H_46M_30S_0MS | S5T#10s, S5TIME#10s | |

S5TIME

- Underscores in time and date are optional

- It is not necessary to specify all time units (for example: T# 5h10s is valid)

- Maximum time value = 9,990 seconds or 2H_46M_30S

| Time base | Binary Code |

|---|---|

| 10 ms | 00 |

| 100 ms | 01 |

| 1 s | 10 |

| 10 s | 11 |

More information:

TIA Datatypes: S7 data types summary table

If you'd like to support the development of the site with the price of a coffee — or a few — please do so here.

If you'd like to support the development of the site with the price of a coffee — or a few — please do so here.

Array

An array is used to group data of the same type into blocks that can be easily addressed, i.e., indexed.

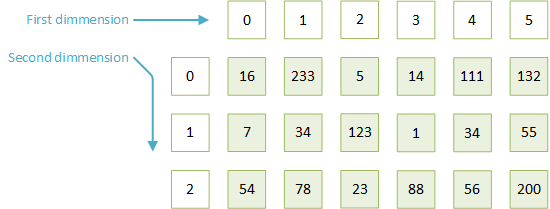

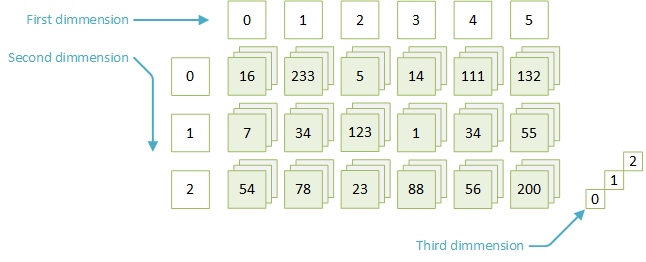

Arrays can be 1-, 2-, or 3-dimensional, or even 6-dimensional. The following example illustrates the structure of 2- and 3-dimensional arrays:

The image above displays a two-dimensional array of type “byte.” The first index represents the rows, while the second represents the columns. The value range of a byte is 0 to 255, so only values within this range are allowed. In the example above, the program's type definition is as follows:

arry : Array[0..5, 0..2] of Byte;

The assignment is displayed in the code like this:

tomb[3, 1] := 1;

The indexing of a three-dimensional array can be illustrated as follows:

In this case, the above assignment can be defined in the program as follows:

tomb[3, 1, 0] := 1;

Array of struct

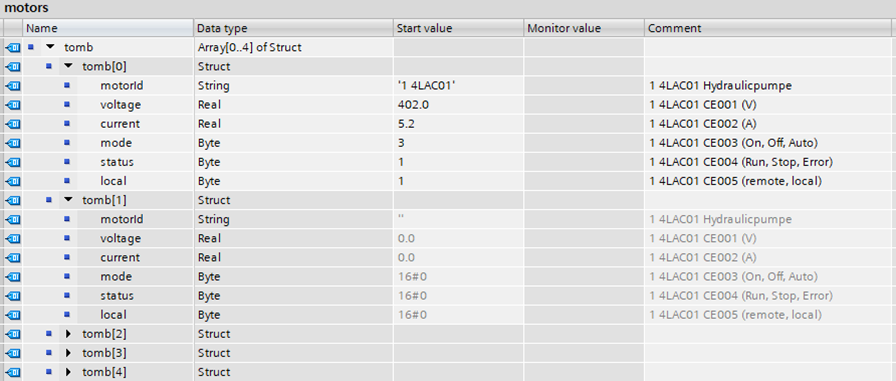

The elements of the array are always homogeneous, meaning their types cannot vary. However, there can be multiple instances of a single type within a single array if we define a Struct type as an array element. The hydraulic motors described as an example in Struct can also be defined as an array:

In this case, I specified the type of the four-element array as “Struct”. Here, a field opens under the name of the first array element (tomb[0]), where the Struct's elements can be defined. It is important that the array is homogeneous, meaning the structure can only be set for the first element; the other elements will be copies of it without the ability to modify the structure (values, of course, can change). In the example above, the value assignment will look like this (the DB name is “motors”):

"motors".tomb[1].current := 32.2;

More information:

TIA Datatypes: S7 data types summary table

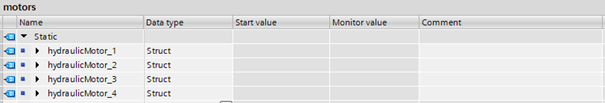

Structure

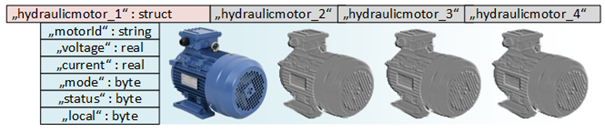

A structure is a way of organizing multiple variables, often of different types, into a group. For example, the characteristics of several devices, such as motors, can be described using the same data groups.

Take an electric motor, for instance. Such a motor can have many technical parameters, but for simplicity, let's narrow down the range of these parameters.

In this case, the motor has a text identifier, typically a KKS identifier in larger installations. Then there are voltage and current measurements, an operating mode, and a status indication. These data belong together and describe a motor. In the example above, this motor is, for example, the first motor of a hydraulic block. In the case of multiple motors, this structure remains—only the parameters change, as this makes it easy to handle the data uniformly:

This is what it looks like in the TIA Portal when the structures are open:

The display of structures can be limited to just their names, with an arrow placed in front of the name to close the content:

More information:

TIA Datatypes: S7 data types summary table

UDT

The structure of the UDT (User Defined Type) is identical to that of the STRUCTURE type; you can create more complex variables from existing variables, structures, and their arrays. The key difference is that while a STRUCTURE is valid within a specific function (FB, FC, OB), a UDT is a universal type that must be defined in a separate library within the TIA Portal (PLC > PLC data types). Variables created from the UDT can be used throughout the entire program, which is especially useful for large-scale functions like communication, where maintaining an identical structure is important. However, when modifying a UDT, be aware that it may sometimes cause the program to crash.

Variables created from the UDT can be used throughout the entire program, which is especially useful for large-scale functions like communication, where maintaining an identical structure is important. However, when modifying a UDT, be aware that it may sometimes cause the program to crash.

The UDTs shown here fall into two categories: The normal UDTs (icon: ) are fully editable and can be modified freely. The locked UDTs (icon:

) are fully editable and can be modified freely. The locked UDTs (icon: ) are connected to closed (typically system) functions; modifying them could cause major issues in the program.

) are connected to closed (typically system) functions; modifying them could cause major issues in the program.

A locked UDT is also shown by an icon ( ) in the corner of the editor window.

) in the corner of the editor window.

PLC data types (UDT) can be nested up to 8 levels deep. Starting from firmware V4.0, CPUs in the S7-1500 series support nesting up to 26 levels. Each ARRAY of STRUCT/UDT uses 3 hierarchy levels.

The UDT type can be imported and exported quickly. To export: right-click on the specific type, choose “Generate source from blocks,” and select “Selected blocks only.” To import: go to PLC, then External source files, click “Add new external file,” right-click the external file, and select “Generate block from source.”

OB, DB, FB, FC

PLCs differ from PCs in several ways. Their structure and programming architecture are simpler and more straightforward. A key difference is that they lack a traditional file system; instead, they consist of four main components:

| Symbol | Description |

| OB – organization block: OBs play a special role in running programs, as they essentially start programs based on various criteria. The simplest is OB1, which runs 'continuously'. As soon as a complete execution cycle ends — that is, all programs started from the OB have run — it restarts them after the signals are output and read. There are scheduled, error-related, and interrupt OBs; more details are available in the OB section. |

| A DB – data block: A DB organizes data based on various aspects and has two primary types. The global DB is created directly by the programmer, whereas the instant DB is a storage block assigned to an FB. For more information, refer to the DB chapter. |

| FC – FB: Throughout the program, modules that are repeated multiple times or are structurally different can be organized into FBs or FCs. This approach is crucial during commissioning and later corrections to ensure the code remains clear and well-structured. For instance, unorganized code 'dumped' into OB1 raises concerns for experienced programmers reviewing the system. Several other red flags exist, where acceptance only occurs if the code is entirely rewritten. | |

| FC – Function. These are basic program blocks that do not pass variables to subsequent cycles. Examples include a module that creates colors in an HMI or a segment that performs mathematical operations. Further details are available in the FC chapter. |

| FB – function block. Each FB is always linked to a Data Block (DB) that holds some of its data. This DB operates independently of cycles. Sometimes, it isn't a unique DB but a multi-instance DB. More information about these can be found in the FB chapter. |

| iDB - instant DB: Although it appears as a standard DB in the TIA Portal without a distinct symbol, I am explicitly identifying this DB type in this document. It is always linked to a specific FB and stores the non-temporary data of that FB. For more information, refer to the DB chapter. |

An example of program calls

- The OB32 calls the FC1 cyclically every 100 ms.

- The FC1 first calls the first inverter, then the second inverter.

- The FB1, whose instant data block is DB12, is called. The FB1 initiates a Modbus Client call (MB_CLIENT_1), which reads its parameters (IP, unitID, etc.) from DB14. Because this FB is embedded within FB1, it receives a multi-instant block in DB12. The results of the Modbus read are written to DB15.

- The second Modbus read operates similarly, with its parameters also in DB14 and its multi-instant block in DB12.

- FC1 is called again, which then calls inverter2, following a similar call sequence as the first case.

- Control returns to OB32, which waits for the next 100 ms cycle and then calls FC1 again.

Data block (DB)

“DB” stands for DATA_BLOCK or the German term “Datenbaustein', indicating a data area. It can contain various data types permitted and defined by the specific PLC. The total size of all DBs is limited by the PLC's data capacity. Since the PLC isn't optimized for storing large data, we do not save images, music, files, or extensive text files within a DB. In the TIA-Portal, DBs are marked with a small blue barrel icon ( ).

The image below shows the contents of a DB, along with some settings:

).

The image below shows the contents of a DB, along with some settings:

The columns are as follows:

| Column | Desription |

|---|---|

| Name | The name of the variable within the DB. The variable names are unique, and the DB name is displayed in the upper-left corner, in this case: K11. The variable names are supplemented with this, e.g., “K11”.liveByte. This also means that the DB can be copied and renamed one-for-one. That is, if this DB is copied and renamed to, for example, “K12”, the above reference will be “K12”.liveByte. In the case of a structure, for example, ”cbUsage“, the entire structure depth must be defined, for example: “K11”.cbUsage.cbOpenClose. |

| Data type | The data type. Structures and arrays must be created when defining the DB by entering, for example, type Struct in the Data type field. |

| Offset | The offset of the variable within the DB. This appears only for non-optimized DBs. More details: optimized DB |

| Start value | The starting value of the given variables, which the PLC takes on when restarting. The default value can be overwritten in the cell. |

| Retain | Values to be retained when restarting. It can only be set for the entire DB, so it is worth grouping the values to be stored in a DB |

| Accessible from HMI/OPC UA/Web API | The value is accessible from external applications. For structures and arrays, the setting can only be defined for the entire block. OPC access can be enabled/disabled in the settings, see DB Properties. |

| Writable from HMI/OPC UA/Web API | The given value can be written from external applications. |

| Visible in HMI engineering | The setting disables or enables the HMI integration of the variable. In addition to disabling HMI, OPC can also be enabled, see DB Properties. |

| Setpoint | This allows you to initialize values in a data block (DB) online while the CPU is in RUN mode. |

| Comment | Description of the function of the field. |

DB Limits

- You can define up to 252 structures within a single data block for S7-1200/S7-1500, regardless of the data types used in the structures.

- Maximum DB Number: The total number of data blocks is generally capped at 65,535, due to the common use of a 16-bit address range.

- Maximum DB Size (Standard - not optimized - Access): For older PLC models like S7-300/400 and for standard access DBs in newer models, each DB's size typically does not exceed 64 KB (65,534 bytes).

- Maximum DB Size (Optimized Access): In contrast, S7-1200/S7-1500 CPUs that utilize optimized access have a much larger size limit, which varies based on the CPU's total working memory and can reach from 1 MB up to 10 MB or more per DB.

Instant vs global DB

A global DB is a data block that programmers can freely create and populate with variables. These variables may include default Simatic types (INT, REAL, etc.), structures, arrays, or UDTs.

Instant DBs are implicitly created when FBs are called for the first time. This call is primarily through the instant DB. When an FB is deleted, the TIA Portal also issues a separate warning about removing the instant DB. The contents of the instant DB automatically update with changes to the FB's variable list. It can include default Simatic variables like INT, REAL, structures, arrays, and UDTs. If the FB calls other embedded FBs (e.g., TON, TOF), their instant DBs are also stored here, resulting in a multi-instant DB.

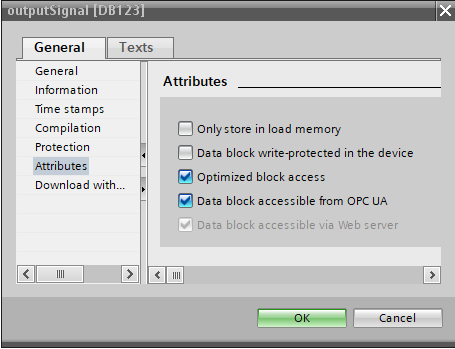

DB Properties

(right-click on the DB → Properties..)

| Name the attribut | Description |

|---|---|

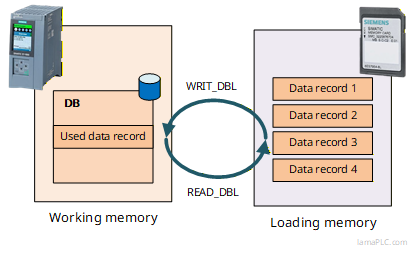

| Only store in load memory | This attribute is stored on the PLC's Micro Memory Card (MMC) or similar non-volatile storage, not in the CPU's working RAM, making it ideal for large, infrequently used data such as recipes or logs. It's accessed using special instructions like READ_DBL or WRIT_DBL to transfer data to/from working memory. This preserves precious working memory, but requires explicit programming to move data for active processing. The data survives power cycles but can be lost with a factory reset. |

| Data block write-protected in the device | Make the entire data block read-only. |

| Optimized block access | Optimized variable order within the DB. See below: Optimized DB. |

| Data block accessible from OPC UA | The data block can be accessed and published by OPC UA. See: OPC UA. |

Optimized DB

Simatic groups variables in the optimized DB so they occupy as little storage space as possible. This means that it is “not visible from the outside” where a given data item is located within the storage space, i.e., in this case, the offset is not displayed in the editor window:

On the one hand, this helps better utilize the PLC's storage space. Still, on the other hand, it makes operations that require direct addressing (communication modules - Modbus, direct addressing, etc.) impossible. In such cases, this option must be disabled in the settings (right-click on the DB → Properties.. → Attributes → Optimized block access → OFF)

Tags vs DB data

There are two basic methods for storing data in PLCs (in a simplified view). One involves placing variables in a global memory table alongside input and output variables, while the other uses data blocks (DBs). From my experience, storing data in DBs tends to be simpler and more straightforward for several reasons.

- Function-specific data can be stored in DBs. For example, the “motor1” DB contains only data for the 1st motor, but all of them (speed, load, temperature, on-off, errors, …)

- If someone wants to define a “motor2” as well, identical to “motor1” in terms of its parameters, they just need to copy the previous DB

- Cross-reference management of data immediately points to the given DB, from which we can immediately deduce their function

- If the data is already in the instant DBs assigned to the FBs, it is easy to embed them in a calling FB to use them as multi-instants.

Typically, I don't bother defining variables within the Tags; creating them directly in the databases suffices—though this is just my personal preference.

Storing DB records in the load memory

In PLCs, working memory is PLC-dependent and often very limited. We may have a lot of information that does not need to be read and written cyclically. Examples include recipe data (a list of technological components), parameter data, or database assignments that are needed only occasionally.

In these cases, one option is to store the data not in working memory but on the SD card and in load memory, and to transfer them only when needed using the “WRIT_DBL” and “READ_DBL” operations.

More information:

TIA Datatypes: S7 data types summary table

Direct/indirect addressing

Addressing methods are mostly tied to variable types, not areas, so the following procedures apply to both DB and Tag variables.

Direct addressing

Direct addressing in Simatic is typically symbolic addressing, meaning in the simplest case we correspond two variables of the same type to each other:

fromReal : Real; fromInt : Int; toReal : Real; toInt : Int; … #toInt := #fromInt; #toReal := #fromReal;

If the types do not match, conversion will help us:

#toInt := REAL_TO_INT(IN := #fromReal);

It is crucial to understand that conversion can lead to data loss. In the example above, the REAL type can store much larger numbers and fractional parts, while the INT only handles smaller integers and rounds off fractions. When converting between variables with different ranges, all values outside the smaller range should be considered. In this case, rather than using an INT, a variable with a broader range should be selected (example DINT, LINT).

Direct addressing is also applicable to STRUCTURE and ARRAY types, provided both sides have identical structures.

Another approach is direct addressing, which involves referring to a variable's sub-elements. Although this method applies to a limited range of variables, it is a simple form of assignment. While it isn't as straightforward as the S7-Classic AT command that many programmers prefer, it is at least available:

Slice addressing

Slice addressing involves dividing a memory region, such as a byte or a word, into smaller segments, such as booleans. With S7-1200 and S7-1500, you can target specific parts within declared variables (only by byte, word, dword) and access segments of 1, 8, 16, or 32 bits.

The following example is a SPLIT function that splits a WORD Input variable into bits:

// FC Input : inWord (Word) // FC output: 16 variable bit0..bit15 (Bool) // splitting #bit0 := #inWord.%X0; #bit1 := #inWord.%X1; #bit2 := #inWord.%X2; #bit3 := #inWord.%X3; #bit4 := #inWord.%X4; #bit5 := #inWord.%X5; #bit6 := #inWord.%X6; #bit7 := #inWord.%X7; #bit8 := #inWord.%X8; #bit9 := #inWord.%X9; #bitA := #inWord.%X10; #bitB := #inWord.%X11; #bitC := #inWord.%X12; #bitD := #inWord.%X13; #bitE := #inWord.%X14; #bitF := #inWord.%X15;

Pointer; indirect addressing

In the TIA Portal, there are two ways to perform indirect addressing or pointer referencing: the ANY and the VARIANT. However, it is important to note that the S7-1200 series PLCs do not support the ANY method. Using a pointer essentially involves moving a data block of a specific size to a memory area of the same size. This operation ignores the structure and variables within the data area, making it a quick and useful method when applied carefully. However, careless use of this tool can be very risky.

A key issue is that it doesn't handle the variables within the data being pointed to; for example, when searching for errors with xref, these procedures are not visible to the compiler, which can lead to difficult-to-detect errors caused by improper pointer use.

ANY type

Structure of the ANY Pointer (10 Bytes):

| Name | Length | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Syntax ID | 1 byte | Always 16#10 for S7 |

| Data Type | 1 byte | Code for the type of data being pointed to (e.g., 16#02 for Byte; see below in the table “TIA Coding of data types” |

| Repetition Factor | 2 bytes | Number of elements of the specified data type |

| DB Numbe | 2 bytes | The number of the data block (0 if not in a DB) |

| Memory Area | 1 byte | Code for the memory area (e.g., 16#84 for DB; see below in the table “TIA Coding of the memory area”) |

| Address | 3 bytes | The start address of the data (bit and byte address) |

TIA Coding of data types

The following table lists the coding of data types for the ANY pointer:

| Hexadecimal code | Data type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| B#16#00 | NIL | Null pointer |

| B#16#01 | BOOL | Bits |

| B#16#02 | BYTE | bytes, 8 bits |

| B#16#03 | CHAR | 8-bit characters |

| B#16#04 | WORD | 16-bit words |

| B#16#05 | INT | 16-bit integers |

| B#16#06 | DWORD | 32-bit words |

| B#16#07 | DINT | 32-bit integers |

| B#16#08 | REAL | 32-bit floating-point numbers |

| B#16#0B | TIME | Time duration |

| B#16#0C | S5TIME | Time duration |

| B#16#09 | DATE | Date |

| B#16#0A | TOD | Date and time |

| B#16#0E | DT | Date and time |

| B#16#13 | STRING | Character string |

| B#16#17 | BLOCK_FB | Function block |

| B#16#18 | BLOCK_FC | Function |

| B#16#19 | BLOCK_DB | Data block |

| B#16#1A | BLOCK_SDB | System data block |

| B#16#1C | COUNTER | Counter |

| B#16#1D | TIMER | Timer |

TIA Coding of the memory area

The following table lists the coding of the memory areas for the ANY pointer:

| Hexadecimal code | Area | Description |

|---|---|---|

| B#16#80 | P | I/O |

| B#16#81 | I | Memory area of inputs |

| B#16#82 | Q | Memory area of outputs |

| B#16#83 | M | Memory area of bit memory |

| B#16#84 | DBX | Data block |

| B#16#85 | DIX | Instance data block |

| B#16#86 | L | Local data |

| B#16#87 | V | Previous local data |

Example of using the ANY type

The pointer with the ANY type is most frequently used with the BLKMOV command, which copies data from one area to another indirectly. In the example below, the created dataset is transferred to one of three mobile data areas based on the location of the variable “assHMI”.Panel1ASS points:

CASE "assHMI".Panel1ASS OF 1: // ASS1 data to disp 1 #state := BLKMOV(SRCBLK := P#db108.dbx0.0 BYTE 72, DSTBLK => P#db108.dbx216.0 BYTE 72); 2: // ASS1 data to disp 2 #state := BLKMOV(SRCBLK := P#db108.dbx72.0 BYTE 72, DSTBLK => P#db108.dbx216.0 BYTE 72); 3: // ASS1 data to disp 3 #state := BLKMOV(SRCBLK := P#db108.dbx144.0 BYTE 72, DSTBLK => P#db108.dbx216.0 BYTE 72); ELSE // Statement section ELSE ; END_CASE;

VARIANT versus ANY

- ANY is a fixed 10-byte structure that references an absolute memory address.

- VARIANT is a type-safe pointer that preserves the original data type information and enables symbolic addressing without the need for fixed memory location overhead.

- The ANY is an older type, already available in the S300 / 400 series.

* The ANY can only be used with the S7-1500, whereas VARIANT are accessible on all S7 models.

VARIANT type

A VARIANT type parameter is a pointer that can reference various data types beyond a simple instance. This pointer can be an object of a basic data type like INT or REAL, or it can be a STRING, DTL, ARRAY of STRUCT, UDT, or an ARRAY of UDT. The VARIANT pointer can also recognize structures and point directly to individual members of those structures. An operand of VARIANT type does not consume space in the instance data block or work memory but does require memory on the CPU.

- Directly assigning a tag to a VARIANT, like myVARIANT := #Variable, is not possible.

- Direct reading or writing of a signal from an I/O input or output is only possible with an S7-1500 module.

- You can only reference a complete data block if it was originally created from a user-defined data type (UDT).

If you'd like to support the development of the site with the price of a coffee — or a few — please do so here.

If you'd like to support the development of the site with the price of a coffee — or a few — please do so here.

TIA Data type limits

| Decimal | Hex | TIA data type | Byte | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18,446,744,073,709,551,615 | FFFF FFFF FFFF FFFF | LWORD, ULINT | 8 | The maximum unsigned 64 bit value (264 − 1) |

| 9,223,372,036,854,775,807 | 7FFF FFFF FFFF FFFF | LINT | 8 | The maximum signed 64 bit value (263 − 1) |

| 9,007,199,254,740,992 | 0020 0000 0000 0000 | - | 8 | The largest consecutive integer in IEEE 754 double precision (253) |

| 4,294,967,295 | FFFF FFFF | DWORD, UDINT | 4 | The maximum unsigned 32 bit value (232 − 1) |

| 2,147,483,647 | 7FFF FFFF | DINT | 4 | The maximum signed 32 bit value (231 − 1) |

| 16,777,216 | 0100 0000 | - | 4 | The largest consecutive integer in IEEE 754 single precision (224) |

| 65,535 | FFFF | WORD, UINT | 2 | The maximum unsigned 16 bit value (216 − 1) |

| 32,767 | 7FFF | INT | 2 | The maximum signed 16 bit value (215 − 1) |

| 255 | FF | BYTE | 1 | The maximum unsigned 8 bit value (28 − 1) |

| 127 | 7F | SINT | 1 | The maximum signed 8 bit value (27 − 1) |

| −128 | 80 | SINT | 2 | Minimum signed 8 bit value |

| −32,768 | 8000 | INT | 2 | Minimum signed 16 bit value |

| −2,147,483,648 | 8000 0000 | DINT | 4 | Minimum signed 32 bit value |

| −9,223,372,036,854,775,808 | 8000 0000 0000 0000 | LINT | 8 | Minimum signed 64 bit value |

TIA Datatypes

List of data types used by Simatic S7. The page contains the more modern TIA variable types as well as the earlier S7-classic types.

List of data types used by Simatic S7. The page contains the more modern TIA variable types as well as the earlier S7-classic types.

There are four data types in: Boolean, Text, Numeric, and Date/Time. Each data type defines the format of information that can be entered into a data field and stored in your database.

| Datatyp | Width (bits) | Range of values | Examples | S7-300/400 | S7-1200 | S7-1500 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binaries | ||||||

| BOOL (x) →details | 1 (S7-1500 optimized 1 Byte) | FALSE or TRUE BOOL#0 or BOOL#1 BOOL#FALSE oder BOOL#TRUE | TRUE BOOL#1 BOOL#TRUE | X | X | X |

| BYTE (b) →details | 8 | B#16#00 .. B#16#FF 0 .. 255 2#0 .. 2#11111111 | 15, BYTE#15, B#15 | X | X | X |

| WORD (w) →details | 16 | W#16#0000 .. W#16#FFFF 0 .. 65.535 B#(0, 0) .. B#(255, 255) | 55555, WORD#55555, W#555555 | X | X | X |

| DWORD (dw) →details | 32 | DW#16#0000 0000 .. DW#16#FFFF FFFF 0 .. 4,294,967,295 | DW#16#DEAD BEEF B#(111, 222, 255, 200) | X | X | X |

| LWORD (lw) →details | 64 | LW#16#0000 0000 0000 0000 .. LW#16#FFFF FFFF FFFF FFFF 0 .. 18.446.744.073.709.551.615 | LW#16#DEAD BEEF DEAD BEEF B#(111, 222, 255, 200, 111, 222, 255, 200) | - | - | X |

| Datatyp | Width (bits) | Range of values | Examples | S7-300/400 | S7-1200 | S7-1500 |

| Integers | ||||||

| SINT (si) →details | 8 | -128 .. 127 (hex only positive) 16#0 .. 16#7F | +42, SINT#+42 16#1A, SINT#16#2A | - | X | X |

| INT (i) →details | 16 | -32.768 .. 32.767 (hex only positive) 16#0 .. 16#7FFF | +1234, INT#+3221 16#1ABC | X | X | X |

| DINT (di) →details | 32 | -2.147.483.648 .. +2.147.483.647 (hex only positive) 16#00000000 .. 16#7FFFFFFF | 123456, DINT#123.456, 16#1ABC BEEF | X | X | X |

| USINT (usi) →details | 8 | 0 .. 255 16#00 .. 16#FF | 42, USINT#42 16#FF | - | X | X |

| UINT (ui) →details | 16 | 0 .. 65.535 16#0000 .. 16#FFFF | 12.345, UINT#12345 16#BEEF | - | X | X |

| UDINT (udi) →details | 32 | 0 .. 4.294.967.295 16#00000000 .. 16#FFFF FFFF | 1.234.567.890, UDINT#1234567890 | - | X | X |

| LINT (li) →details | 64 | -9.223.372.036.854.775.808 .. +9.223.372.036.854.775.807 | +1.234.567.890.123.456.789, LINT#+1.234.567.890.123.456.789 | - | - | X |

| ULINT (uli) →details | 64 | 0 .. 18.446.744.073.709.551.615 | 123.456.789.012.345, ULINT#123.456.789.012.345 | - | - | X |

| Datatyp | Width (bits) | Range of values | Examples | S7-300/400 | S7-1200 | S7-1500 |

| floating point numbers | ||||||

| REAL ® →details | 32 | -3.402823e+38 .. -1.175 495e-38 .. +1.175 495e-38 .. +3.402823e+38 | 0.0, REAL#0.0 1.0e-13, REAL#1.0e-13 | X | X | X |

| LREAL (lr) →details | 64 | -1.7976931348623158e+308 .. -2.2250738585072014e-308 .. +2.2250738585072014e-308 .. +1.7976931348623158e+308 | 0.0, LREAL#0.0 | - | X | X |

| Datatyp | Width (bits) | Range of values | Examples | S7-300/400 | S7-1200 | S7-1500 |

| Times | ||||||

| S5TIME (s5t) →details | 16 | S5T#0H_0M_0S_0MS .. S5T#2H_46M_30S_0MS | S5T#10s, S5TIME#10s | X | - | X |

| TIME (t) →details | 32 | T#-24d20h31m23s648ms .. T#+24d20h31m23s647ms | T#13d14h15m16s630ms, TIME#1d2h3m4s5ms | X | X | X |

| LTIME (lt) →details | 64 | LT#-106751d23h47m16s854ms775us808ns .. LT#+106751d23h47m16s854ms775us807ns | LT#1000d10h15m24s130ms152us15ns, LTIME#200d2h2m1s8ms652us315ns | - | - | X |

| Timer operations: IEC timers, TON (Generate on-delay), TOF (Generate off-delay), TP (Generate pulse), TONR (Time accumulator) | ||||||

| Datatyp | Width (bits) | Range of values | Examples | S7-300/400 | S7-1200 | S7-1500 |

| Counters | ||||||

| CHAR →details | 8 | ASCII character set | 'A', CHAR#'A' | X | X | X |

| WCHAR (wc) →details | 16 | Unicode character set | WCHAR#'A' | - | X | X |

| STRING (s) →details | n+2 (Byte) | 0 .. 254 characters (n) | 'Name', STRING#'lamaPLC' | X | X | X |

| WSTRING (ws) →details | n+2 (Word) | 0 .. 16382 characters (n) | WSTRING#'lamaPLC' | - | X | X |

| Counter operations: CTU (count up), CTD (count down), CTUD (count up and down) | ||||||

| Datatyp | Width (bits) | Range of values | Examples | S7-300/400 | S7-1200 | S7-1500 |

| Date & time | ||||||

| DATE (d) →details | 16 | D#1990-01-01 .. D#2168-12-31 | D#2020-08-14, DATE#2020-08-14 | X | X | X |

| TOD (tod) (TIME_OF_DAY) →details | 32 | TOD#00:00:00.000 .. TOD#23:59:59.999 | TOD#11:22:33.444, TIME_OF_DAY#11:22:33.444 | X | X | X |

| LTOD (ltod) (LTIME_OF_DAY) →details | 64 | LTOD#00:00:00.000000000 .. LTOD#23:59:59.999999999 | LTOD#11:22:33.444_555_111, LTIME_OF_DAY#11:22:33.444_555_111 | - | - | X |

| DT (dt) (DATE_AND_TIME) →details | 64 | Min.: DT#1990-01-01-0:0:0 Max.: DT#2089-12-31-23:59:59.999 | DT#2020-08-14-2:44:33.111, DATE_AND_TIME#2020-08-14-11:22:33.444 | X | - | X |

| LDT (ldt) (L_DATE_AND_TIME) →details | 64 | Min.: LDT#1970-01-01-0:0:0.000000000, 16#0 Max.: LDT#2262-04-11-23:47:16.854775807, 16#7FFF_FFFF_FFFF_FFFF | LDT#2020-08-14-1:2:3.4 | - | - | X |

| DTL (dtl) →details | 96 | Min.: DTL#1970-01-01-00:00:00.0 Max.: DTL#2554-12-31-23:59:59.999999999 | DTL#2020-08-14-10:12:13.23 | - | X | X |

| Datatyp | Width (bits) | Range of values | Examples | S7-300/400 | S7-1200 | S7-1500 |

| Pointers | ||||||

| POINTER (p) →details | 48 | Symbolic: “DB”.“Tag” Absolute: P#10.0 P#DB4.DBX3.2 | X | - | X | |

| ANY (any) →details | 80 | Symbolic: “DB”.StructVariable.firstComponent Absolut: P#DB11.DBX12.0 INT 3 P#M20.0 BYTE 10 | X | - | X | |

| VARIANT (var) →details | 0 | Symbolic: “Data_TIA_Portal”. StructVariable.firstComponent Absolute: %MW10 P#DB10.DBX10.0 INT 12 | - | X | X | |

| BLOCK_FB | 0 | - | X | - | X | |

| BLOCK_FC | 0 | - | X | - | X | |

| BLOCK_DB | 0 | - | X | - | - | |

| BLOCK_SDB | 0 | - | X | - | - | |

| VOID | 0 | - | X | X | X | |

| PLC_DATA_TYPE | 0 | - | X | X | X | |

TIA Coding of data types

The following table lists the coding of data types for the ANY pointer:

| Hexadecimal code | Data type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| B#16#00 | NIL | Null pointer |

| B#16#01 | BOOL | Bits |

| B#16#02 | BYTE | bytes, 8 bits |

| B#16#03 | CHAR | 8-bit characters |

| B#16#04 | WORD | 16-bit words |

| B#16#05 | INT | 16-bit integers |

| B#16#06 | DWORD | 32-bit words |

| B#16#07 | DINT | 32-bit integers |

| B#16#08 | REAL | 32-bit floating-point numbers |

| B#16#0B | TIME | Time duration |

| B#16#0C | S5TIME | Time duration |

| B#16#09 | DATE | Date |

| B#16#0A | TOD | Date and time |

| B#16#0E | DT | Date and time |

| B#16#13 | STRING | Character string |

| B#16#17 | BLOCK_FB | Function block |

| B#16#18 | BLOCK_FC | Function |

| B#16#19 | BLOCK_DB | Data block |

| B#16#1A | BLOCK_SDB | System data block |

| B#16#1C | COUNTER | Counter |

| B#16#1D | TIMER | Timer |